Movement Stories: A. Schild 1706

Another interesting vintage automatic movement crossed my bench the other day. This was an A. Schild (AS) 1706, in this case cosplaying as a Wittnauer 11AO (more on that later).

When I received the watch containing this movement, I noted immediately that it would not take a wind. For manual-wind watches, 9 times out of 10 that means a broken mainspring, but broken mainsprings are extremely rare in automatic watches - and when they do break it’s usually at the bridle end, with the watch still able to take at least a partial wind. The other 10% of the time, the winding issue is caused by something going haywire in the keyless works, causing the sliding clutch to not engage, so that’s what I expected to find when I pulled this guy out of the case. Instead, I was surprised to find the ratchet wheel, as well as the screw that normally attaches it to the mainspring arbor, had completely separated from the movement! At first I thought perhaps the screw had stripped, but this was not the case. Instead, it had somehow completely backed out of the arbor, but how?

In most movements, this would be essentially impossible, as (by design) the act of winding tends to tighten the ratchet wheel screw, not loosen it. But this movement has an interesting and somewhat unconventional automatic winding mechanism which I believe was the culprit in this case. Let’s dig in…

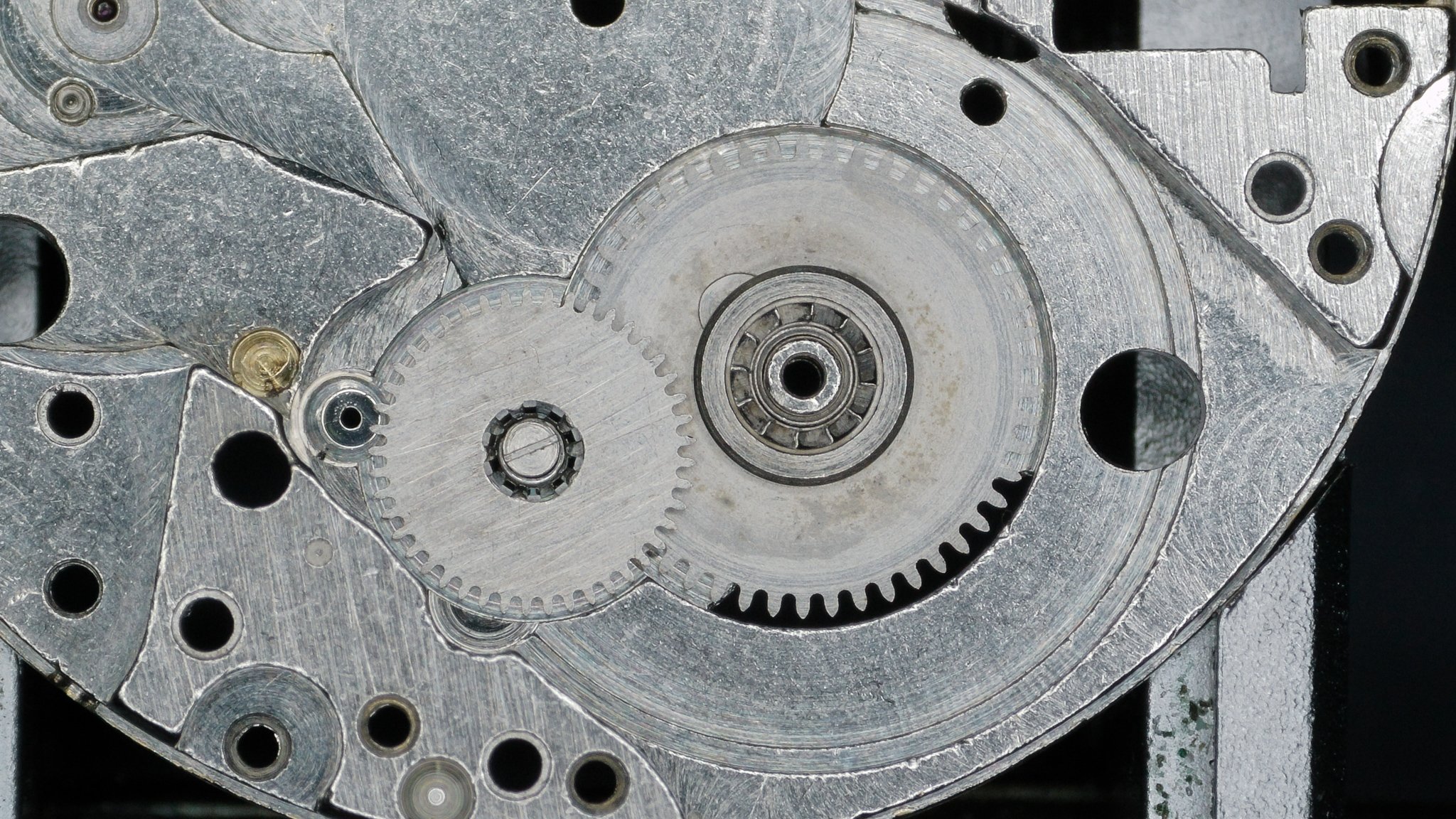

Most of the automatic winding designs I am familiar with drive either the ratchet wheel or the crown wheel in order to wind the watch, and thus the forces they place on the ratchet wheel are essentially similar to hand winding. In the AS 1706, however, the automatic winding mechanism instead engages a pair of final drive wheels that sit underneath the mainspring barrel. These are pictured below:

A closeup of the automatic final drive wheels for the AS 1706. You can see the lower bushing for the wheel that transfers power from the rotor next to the smaller of the two wheels

The larger of these wheels sits directly underneath the mainspring barrel, and has a spring-loaded pawl that engages ratchet teeth on the bottom of the mainspring arbor:

A closeup of the AS 1706 mainspring arbor, showing the ratchet teeth on the side opposite the square drive for the ratchet wheel

Thus, unlike most automatic movements, the mechanism in the AS 1706 directly engages the mainspring arbor for automatic winding. This explains how the ratchet wheel screw could back out: the force exerted on the ratchet wheel during automatic winding - drag from the click and crown wheel - actually tends make the wheel want to spin counter-clockwise relative to the arbor. This force, together with the small amount of slack in the square drive interface for the arbor, could make the ratchet wheel screw back out over a long period of time, especially if the watch is rarely, or never, hand-wound. Hand winding will still tend to tighten the screw, so unlike most automatic movements, you could say that in the AS 1706 a bit of occasional hand winding is actually a good thing!

In any event, to try to ensure this doesn’t happen again, I was careful to fully tighten the ratchet wheel screw when I reassembled this movement. Watchmakers can be a bit casual about tightening this screw fully, since in most movements it tends to tighten itself, but in this movement it’s essential! One reason this gets neglected is that manual tightening is a bit awkward given the fact that the mainspring arbor wants to spin when the screw is turned clockwise. I usually use my plastic pointer to “jam” the click when I tighen these, so the arbor can’t spin and I can get good torque on the screw.

So, with that mystery out of the way, let’s talk about a few other interesting features of this movement. You can see the layout of the train wheels in the picture below:

Closeup of the AS 1706 train wheels before train bridge installation

As you can see from the photo, the layout is very compact, particularly for a sub second watch. In fact the 4th wheel, carrying the sub second hand, actually sits outside of the escape wheel. I believe this layout was chosen because it is easy to convert to a direct-drive sweep second layout by simply moving the 4th wheel to a mirror image position on the other side of the escape and 3rd wheels, directly over the center wheel. One benefit of this compact layout, other than design flexibility, is that it leaves plenty of space to attach the automatic bridge directly to the main plate, contributing to a slimmer, and stronger, movement. You can see all of this extra real estate in the photo below, showing the movement without the automatic bridge installed:

AS 1706 without the automatic bridge installed. Note the large sections of exposed main plate on the upper left and lower right sides of the movement where the automatic bridge attaches

Speaking of the automatic bridge, because the final drive wheels and the decoupling ratchet for the automatic winding mechanism sit underneath the mainspring, the portion of the mechamism attached to the automatic bridge is quite simple, consisting entirely of the rotor, two reversing wheels, and a coupling wheel with a long pinion that extends through the movement and transfers power to the final drive. This simple layout, pictured below, helps keep the movement as thin as possible:

Underside of the AS 1706 automatic winding mechanism. These components are held in place by a thin bridge which attaches to the screw holes visible in the upper left and lower right

One last interesting feature is the retaining mechamism for the automatic winding rotor. This consists of a shim that fits underneath a lip in the rotor shaft and rotates into place by turning a small screw. The shim has a small post projecting upward which mates with a hole in a covering plate, which is in turn held on by another screw. One nice thing about this design is that you can loosen the screw holding the cover plate, and then rotate the shim and release the rotor by turning the other screw without removing any other parts:

Full view of the AS 1706 with the automatic winding bridge and rotor attached

One small oddity I wanted to touch on before I wrap up. As I mentioned this movement is labeled by Wittnauer as a type “11AO.” While it is not unusual for watch manufacturers to mark ebauche movements with their own in-house designations, you can ususally still find the stamp of the movement manufacturer (A. Schild in this case) somewhere on the movement. However, Wittnauer seemingly went out of their way to erase the A. Schild identity from this movement, as someone took the trouble to actually machine away the spot where the AS logo would go, while leaving the 1706 caliber designation:

Spot on the main plate where the AS logo has apparently been expunged

I don’t know how common this practice was with ebauche watch movements. Personally, I have only seen this done in one other movement that I have worked on. I assume it was done with A Schild’s approval, but I’m really not sure why. It’s honestly not that hard to figure out who really made this movement, and in any event only watchmakers would ever see the AS logo even if it wasn’t so carefully erased. If anyone reading this has a clue why this was done, please leave a comment and enlighten me!